Historians will lead you to believe it was all a misunderstanding. How the Americans, in their ignorance, failed to appreciate the differences between Apache bands, between raiding and warfare, how they had a tin ear for language and other cultures. The implication is that if only the Americans were not so stubborn, so unreasonable, so racist, things may have worked out differently.

I don’t think there was a misunderstanding at all. The Americans were here to do what they had always done – take ground from the natives, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. They had shown little aptitude for language and no interest in nuance, or culture, or diplomacy through their history, there is little reason to believe it would change when they arrived in the Southwest. Things were simple then. Men were men and everything moved on horseback – soldiers and supplies, settlers and their families, information. Horses were necessary to travel long distances and short.

A culture tied to the land

The Apaches were stealthy, swift, fierce when provoked, and had fought Spain, then Mexico, for centuries. They lived beyond the range of Mexico City’s armies, and were a major reason that the northern reaches of the territory these nations had staked out remained largely unsettled. But these newcomers, the Americans, had no intention of governing the Arizona Territory from affair, or lose interest when the goldfields ran dry. They’d keep digging, for silver, copper, lead. They were coming.

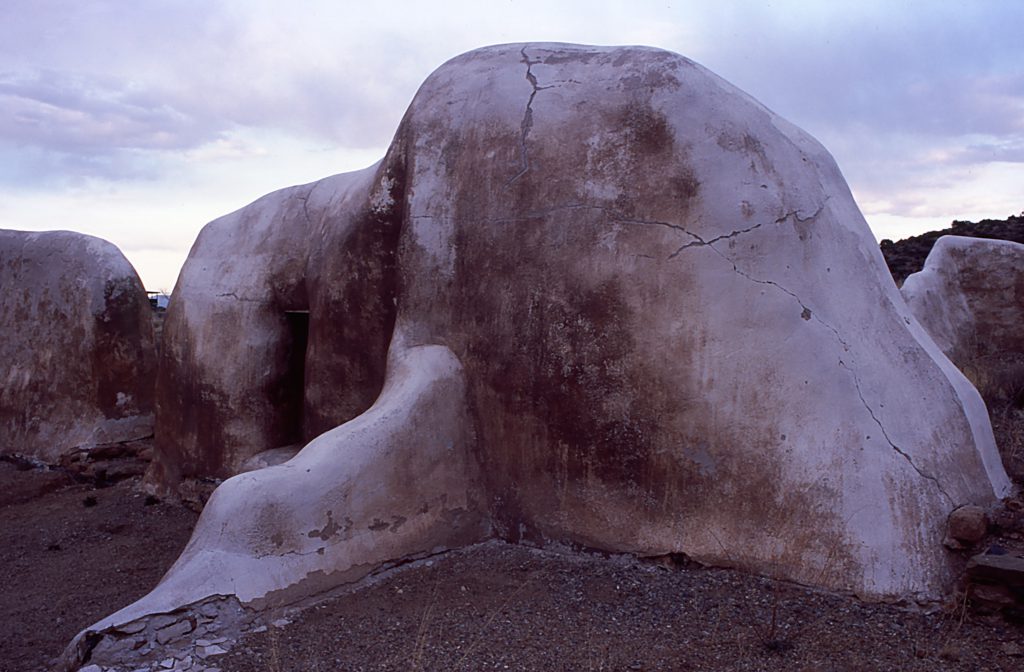

Apache culture was nomadic, living a life that sent them in search of wild plants – agave, pinion, acorns and cactus fruit, as well as elk, deer and small game. They lived in domed shelters called wickiups and traveled with the season, living in the desert during the winter and in higher elevations during the summer months. They could travel long distances quickly, distances that some historians seem to dismiss as hyperbole – 50, 60 miles a day, though I believe these numbers: Today, suburban white folks call this an ultra marathon, something they do for recreation. This ability to move long distances quickly, as well as the terrain of Arizona and New Mexico, made military campaigns against the Apaches difficult.

Broken promises

The Apaches never rallied to one leader. Soldiers and settlers rarely picked up on this, or saw the differences between the various bands and groups. For years, they thought that Cochise, the great Chiricahua leader, spoke for all Apaches. He did not. The Western Apaches, who planted crops and stayed close to their farms in the summer, got along with the Chiricahua, but did not answer to them.

There were efforts to keep the peace. The Tonto signed a treaty as early as 1852. White Mountain Apache chief Eshkeldahsilah went to Fort Goodwin in 1864 to talk to the white soldiers, setting fire to brush along the way so his people would see the gray smoke and know he was safe. The Chirichua leaders Mangas Coloradas, and then Cochise, tried to reason with the Americans, but found it frustrating.

None of these attempts to keep the peace worked out. Promises made were forgotten. Negotiations took bitter turns, and the fact that the Apaches liked to pinch livestock continued to be a problem. Historians will point out that usually, Apaches raiders came quietly in the night, trying to avoiding conflict, stealing a few animals and moving on. But life was messy then, as it is now, and sometimes they got caught. Shots were fired, blood spilled, vengeance necessary, a spiral that today we call history.

Woolsey rides

In central Arizona, a settler named King Woolsey tried his hand at ranching near Prescott, along “well established Apache trails,” one biographer wrote. Not surprisingly, Apaches frequently stole his livestock. The U.S. Army presence in Arizona was small then, so Woolsey, frustrated that the army was not more responsive to his complaints, rallied local settlers from the Prescott area, enlisted the help of scouts from other tribes, and rode off to chastise the Indians.

Woolsey’s vigilantes managed to surprise some Apaches in their camps, where they killed men, women and children. On one expedition, Woolsey led about 75 men deep into Apache territory, where they found themselves outnumbered by a large group of warriors – most accounts put the number around 400. They tricked the Apache leaders into a parley, shot several of them, and fled as the bands reorganized. Because the parties shared some pinole, an Apache corn mixture, during the parley, the incident was later called the Pinole Treaty, and helped seal Woolsey’s reputation as “one of Arizona’s frontier heroes,” historian Katrina Jagodinsky writes.

The politician

In July of 1864, a 10-year-old girl named Lucia Martinez, who had been captured by Apaches, escaped her captors and began the journey back to her southern Sonoran home, more than 200-miles away, Jagodinsky writes.

Just “a few miles” into her escape, the Yaqui girl wandered into Woolsey’s camp of vigilantes. When the expedition returned home a short time later, Woolsey took her to his ranch. Woolsey, who was born and raised in the slave-holding South, ran his ranches according to a Southern code that divided the help according to race. He put the young Yaqui girl to work in the kitchen. Three years later, she bore him a child.

Some of his contemporaries called Woolsey out for killing Indian women and children, but his excursions into Apache country made him a bit of a local celebrity among the population at large, so his neighbors sent him off to represent them in the first Territorial Legislature. Woolsey and his fellow lawmakers approved a legal code nearly 500 pages long that governed the conduct of men, women, minors, adults, whites and Indians, citizens and slaves. The code fixed the age of sexual consent for females at 10, said Jagodinksy. Lucia bore two more of Woolsey’s children before he married a respectable Southern woman. Lucia and the kids were forced into the background.

Things fall apart

The U.S. Army did not put a lot of resources into Arizona during the Civil War. The Apaches thought the newcomers had gone away, but they came back with a vengeance and began to settle, which led to conflict. American troops struggled with the Apaches until General George Crook arrived and began to use Apache scouts. Most of them were Western Apaches, a distinction that Crook had learned to appreciate, when many of his colleagues did not.

By this time, Eshkeldahsilah had come to mistrust the Americans, and considered his options, but ultimately his people joined the Cibecue bands to serve as scouts. Crook used small, mobile patrols led by these scouts, and the Tonto bands were quickly persuaded to stop fighting. The Chiricahua bands were not. For years, they used the border to their advantage, slipping away into Mexico to avoid pursuit.

Crook told the Apaches the Americans were here to stay, and the Apache way of life was over. But he respected the Apaches, more than his colleagues. He told them the truth, expressed confidence in their intelligence and ability to take on a new way of life. Years later, when the Apaches were all on reservations, and word reach them of Crook’s death, some wept.

Adapted from He is Constantly Angry: Eshkeldahsilah, White Mountain Apache Chief, New Mexico Historical Review, Spring, 2006, and ‘Inglorious Arizona: Yesterday’s hero is today’s villain,’ The Arizona Republic, May 23, 2016.