Arizona is losing its history.

Rats build nests in historic documents, old buildings sag and buckle, roofs leak and records blacken with mold. Collectors slip a few papers into their collections and looters plunder archeological sites. Historians and archivists say the problem is getting worse as budgets are slashed and as information is processed digitally, then deleted.

To understand why records matter, it is important to understand that Google doesn’t know everything and history books don’t always get it right.

Some people think history is dry and tedious – all those dates and proper nouns, but strip away history to its raw components, and you have stories of men and women who are not all that different from people today – hungry, horny, greedy, kind and gentle. History is one tale after another of cultural change, migration, hysterical mobs, hate, superstition, love and compassion. The first draft comes in newspapers and books by people who were there. Sometimes these stories are handed down accurately, sometimes not. Historians like to check those early drafts, and the only way to do that is to look back at old diaries, government records and other sources.

The bulk of the state’s history remains on paper, microfilm or microfiche – photographs, diaries, census reports, school records, council minutes, newspapers, tax logs, maps and diaries. These documents leave paper trails of land ownership, policy and taxation, arrests, trials, the decisions on which government, our legal system and daily life are based. Yes, these documents can be digitized, but they usually aren’t.

Detectives at work

One archivist told me about a family that came into the state archives as a last resort. They had been

working a ranch since the 1870s, she said, and found themselves in a dispute over water rights. The state archives had all the assessment rolls for their county, she said, which showed the family had paid a water assessment that went back to Territorial times. A record saved the family’s ranch. Archival records are not just for academics, genealogists or hobbyists.

“Historians have to kind of be detectives,” Juan Garcia, Professor of History and Mex.-American Studies at the University of Arizona told me. “Historians are in essence putting together a puzzle.” When pieces of that puzzle are missing, the historian hits a dead end. Like a biologist who has run out of DNA strands, an astronomer with a blurry telescope, a prosecutor without a witness, the historian can only speculate when information is missing.

“Sometimes the discovery of a primary source … can change an interpretation of how a historical event has been presented before,” Garcia said. Primary sources can allow researchers to expand, affirm or dispute the work of others.

“Primary documents are not infallible, but historians can go back to the documents and evaluate the evidence for themselves,” Garcia said. The digital world has not made piecing together the historical puzzle any easier. If anything, it has made it harder.

Although some collections, or parts of collections, have been digitized, most have simply been catalogued. To digitize the entire collection would require scanning thousands of documents, books, letters, notebooks and articles, one at a time – a time-consuming, expensive process. The reality is that most archival material has not been digitalized, and probably won’t be any time soon.

How technology keeps swallowing the past

The rapidly changing nature of technology creates another problem as machines and recording devices become obsolete. Retired archivist Melanie Sturgeon recalled a conference that took place in 2000, where “we talked about the black hole that we’re already starting to see.”

The State Library and Archives has former Governor Evan Mecham’s impeachment trials on tape, for example, but the tapes are VHS. The library keeps old machines on hand to look at old records, but it gets more difficult with each new generation of technology. Machines, devices and gadgets quickly become relics: Reel to reel, cassette, VHS, beta, floppy. CDs, which are giving way to thumb drives, are easily corrupted. Web sites are taken down and links break.

“I can’t find a computer that takes a floppy disc,” Garcia said. “I’ve called around and asked around and people look at me like I’m very strange.”

The nature of technology also means that people frequently don’t save drafts, he said. There are several drafts available of the Constitution of the United States, for example, and you can see how the document evolved, Garcia said. People used to write letters, and save them. Today they write e-mails, which get deleted.

“With the electronic age it goes into cyberspace and we may never get it back again. So I tell my students we may know more about something that happened 500 years ago than something that happened 10 years ago.”

Where are you from?

One of the biggest reasons that Arizona is losing its history is that a lot of people who live here, are not from here. This is especially true in Phoenix, city of transplants. Ask someone where they’re from and they’ll say “Ohio.” Then you find out they’ve lived here 50 years, one archivist told me. They belong to the historical society – the one that back “home,” in Ohio.

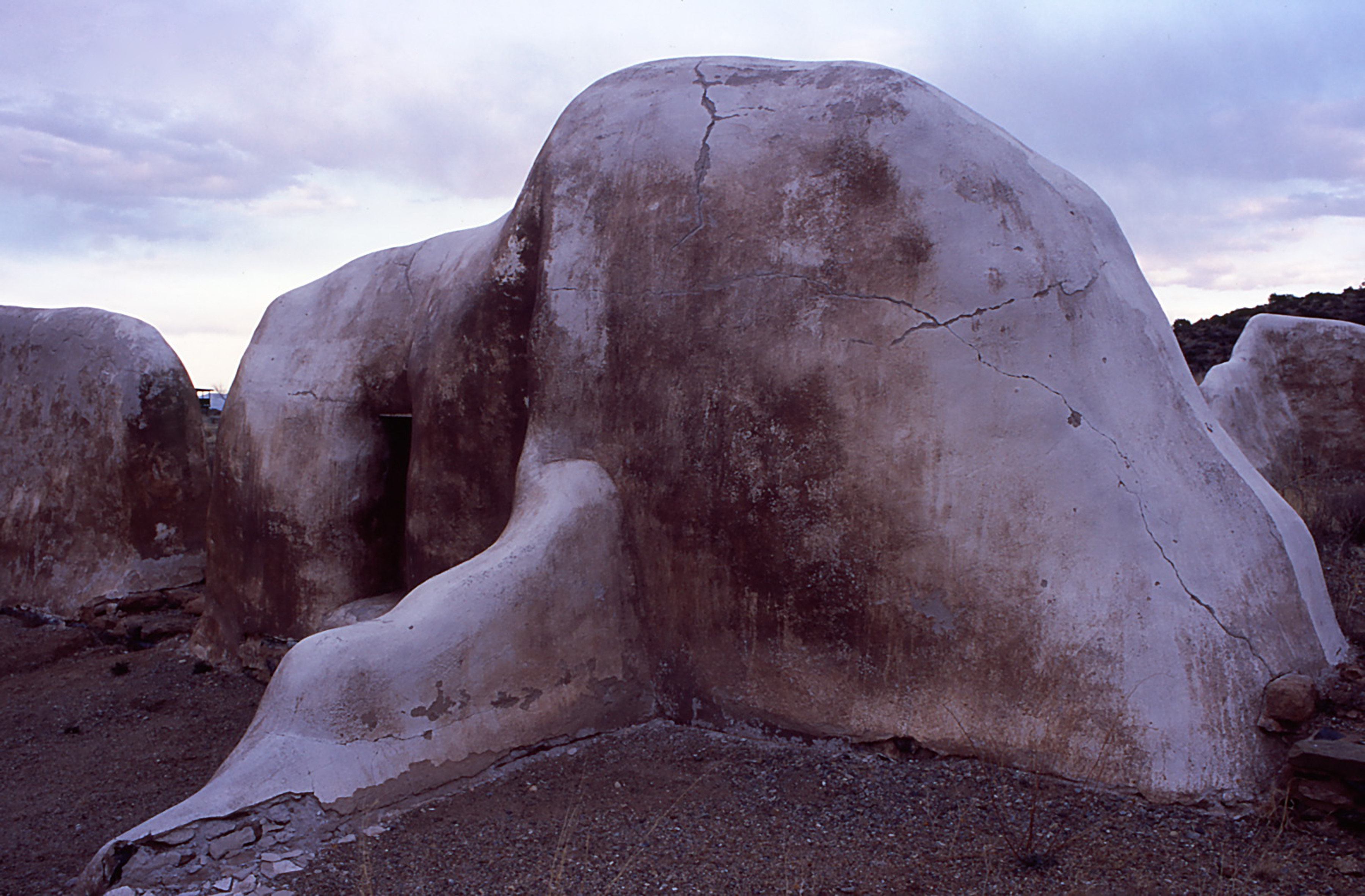

Because Arizona is a young state, people assume that it doesn’t have much of a history. But people lived here before statehood, and their stories go back centuries. There’s Old Oraibi, settled in 1100 AD and possibly the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America. There’s San Xavier, a mission founded by Father Eusebio Kino in 1692. There’s a collection of books and documents going back to the Lincoln administration, stored in a massive concrete structure not far from the state capitol. There’s the state Constitution, there are records of land ownership and water rights that go back to territorial days.

Like public lands, they belong the people, and they deserve to be protected.

This is only tangentially related, but something that really concerns me about the elimination of cursive writing from school curricula is that people will lose their ability to read many primary sources. A letter by your great-grandmother, say, might one day be accessible only to scholars. And when ordinary people can’t easily read these documents, many will be lost or destroyed.

An unusual but illustrative example of this is Turkey, where the language reforms of the 20th Century rendered Ottoman Turkish incomprehensible to ordinary Turks. Even spoken Turkish was affected – for instance, by the 1950s, political speeches recorded in the 20s and 30s needed subtitles. Written sources fared even worse, and hundreds of years of history are now being erased as caches of documents are being destroyed, because only specialists can make anything of them.

I very much enjoy history. good post I am sure you will find like minded folks Cheers